Chapter 14

What is Truth?

Why we paint the truth in shades of gray

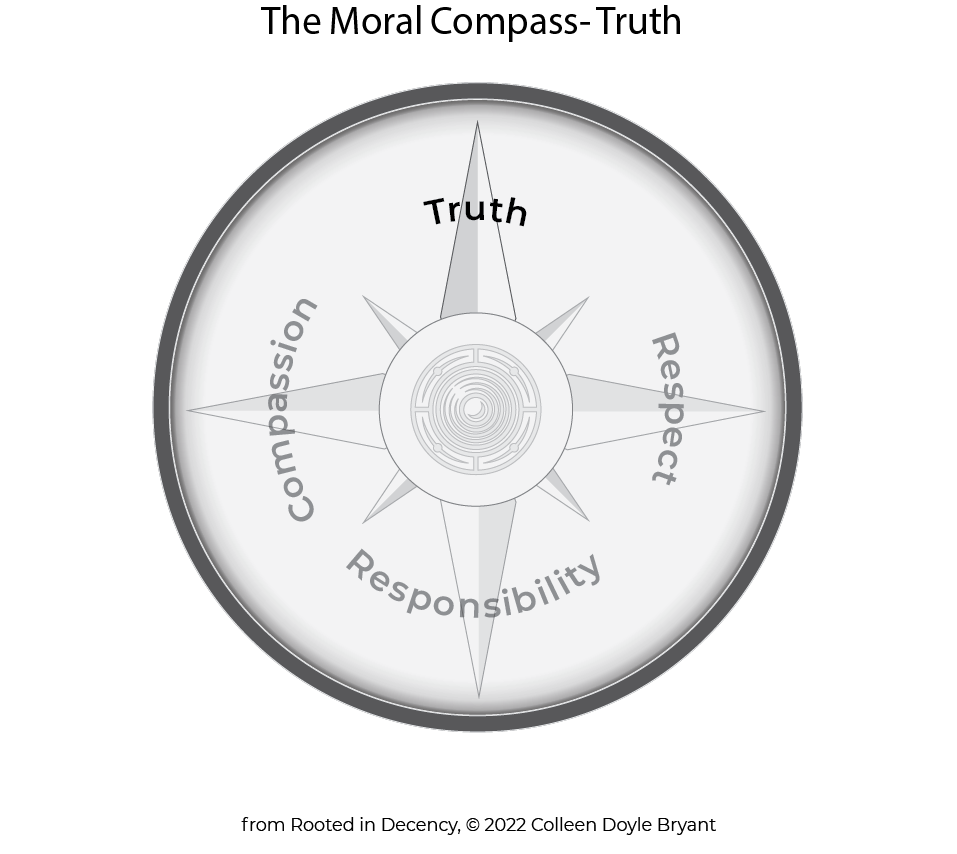

We all bend the truth sometimes. We spin a little to soften the hard truths; we embellish to make ourselves look better; we dramatize to capture attention. But when does bending the truth go too far? Few people would argue that malicious lies told to hurt someone are ever morally acceptable. Yet, how many of us actually expect to be told the cold, hard truth, all the time? Honesty may be the best policy, but there are a lot of gray areas around how much truth we choose to share. And today, a whole industry exists around selling us lies that we’re all too eager to believe. In this age when people toss around the idea of a “post-truth” era, what even is truth and why does it matter? If truth is to take its place as a guiding direction on our moral compass, the first thing we need to do is establish what truth—and truthful behavior—are.

Defining truth

What is Truth?

The truth is factual and objectively accurate. It’s the way things really are and the way they really happened, unaltered by spin, manipulation, or wishful thinking.

The truth is factual and objectively accurate. It’s the way things really are and the way they really happened, unaltered by spin, manipulation, or wishful thinking. If we’re being honest with ourselves, we have to separate what we want to be true—what we feel should be true— from the actual facts that exist in reality. Real truth is based on reliable, accurate, relevant evidence.[1]

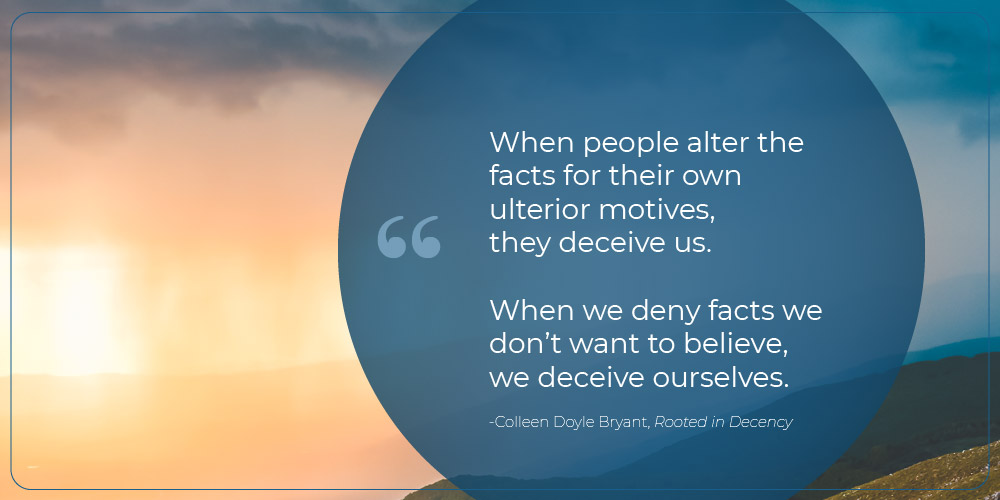

Here’s the tricky bit: People can look at the same truthful information and see things differently. We can have different perspectives about the same facts. But as for the facts themselves—they’re either accurate or they’re not. When people alter the facts for their own ulterior motives, they deceive us. When we deny facts we don’t want to believe, we deceive ourselves. In The Post-Truth Con," we’ll look more in-depth at deception and modern life. For now, we first need to recognize that truth is based in factual reality, whether we like the truth or not.

Truth as a common value

What is Honesty?

To speak and act in a way that represents things as they are in factual reality. One's words, actions, and intentions are genuine, free from falsehoods or deceit.

When we talk about truth on our moral compass, we’re talking about how we act with regard to the truth. Being truthful means that we speak and act in a way that represents things as they are in factual reality. Our words, actions, and intentions are genuine, free from falsehoods or deceit. Truthfulness includes other specific virtues like honesty, sincerity, authenticity, and trustworthiness. The world belief systems we saw in chapter 12 had a lot to say about truthfulness. Here’s a quick summary:

True speech– Using words that accurately represent what we mean; not exaggerating or downplaying; not making false accusations or claims; not spreading false information. Lying, gossip, and rumor are forms of dishonest speech.

True intentions– Being honest with oneself and others about why we are doing something; being free of false pretense. Two vices that show a lack of true intentions are 1) rationalizing, which is when we create irrelevant or false reasons to justify choices and 2) hypocrisy, which is when we hold others to a moral standard that we don’t live up to ourselves.

True action– Being honest about what we are doing. Our actions match our words. Deception, cheating, and manipulation are all forms of dishonest action. We can also deceive ourselves, particularly about our true intentions or the real consequences of our actions.

Truth telling in real life

I can hear you sighing. That’s a pretty high standard for being truthful and frankly we’re not living up to it. But realistically, can we? Should we, in all instances, tell the exact facts, as they happened, in their entirety? Maybe not:

Storytelling would be boring– “To be honest, I caught an average-size fish and it required very little skill.”

Social situations would be awkward– “Truthfully, your husband is not funny; he’s obnoxious. And I can’t wait for you both to leave.”

Negotiation strategy would become irrelevant– “I’m truly desperate for you to make this deal, so just tell me what you’re willing to pay and I’ll agree to it.”

Certainly, there are times when telling the-whole-truth-and-nothing-but-the-truth is the right and only option (like when we’re under oath.) But the complete truth, all the time, in every situation? That’s not how we really live. Social niceties, white lies, and skillful deceptions are part of how we manage to cooperate and to compete while also being respectful and compassionate with each other. The question is, where are the lines between bending the truth and committing a moral wrong?

The truth in black, white, and shades of gray

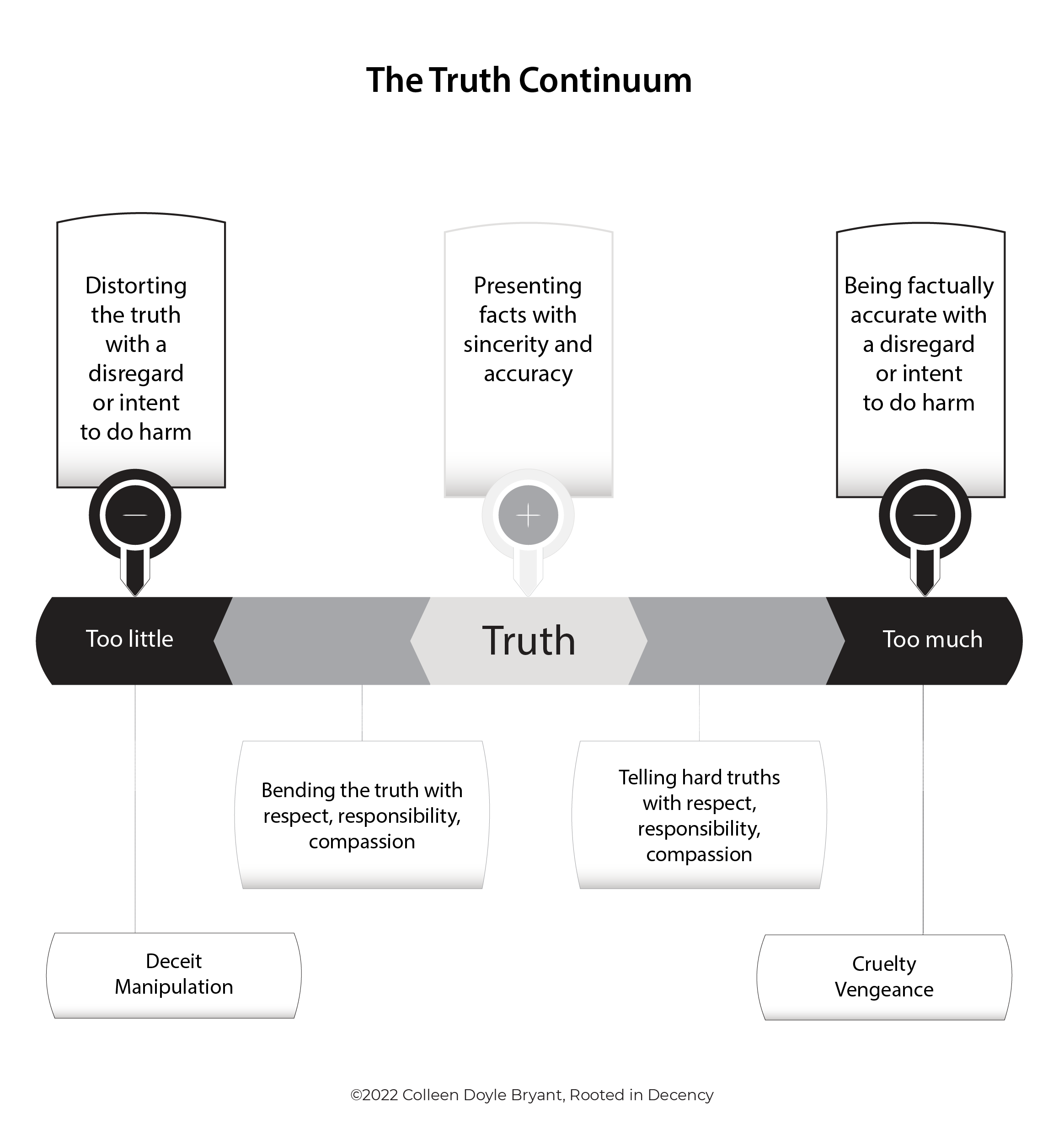

If the morality of truth telling isn’t as simple as “always telling the truth” and “never telling a lie,” then we need a different way to gauge whether we’re being morally truthful. To echo Aristotle, we need to know how to tell the right amount of truth, in the right way, for the right motive. So let’s take a cue from this ancient wisdom and put truth on a continuum that shows a full range of blacks, whites, and grays—from too little truth to too much truth. With a continuum, we take absolutes out of the picture and welcome the nuance that is real life.

We’ll see what too little truth looks like– What’s the difference between a polite white lie and a morally wrong deception?

We’ll see what too much truth looks like– What’s the difference between telling someone a hard truth they need to hear and selfish cruelty?

The truth continuum will help us navigate the gray areas where we balance being truthful with our concerns about treating people with respect, responsibility, and compassion. Sound confusing? Don’t worry—we have infographics.

The Truth Continuum

Take a browse through the Truth Continuum. To help it make sense, think of the story of Goldilocks—some amount of truth is just right, but some amounts are too much or too little. Let’s walk through it, starting in the middle of the continuum with morally good truth.

THE GOOD, HONEST TRUTH

Looking at the middle of our truth continuum, we can see that morally good truthfulness is about presenting facts as they really are, with a sincere intent to be accurate. It’s important to note that in morality, intent matters. If we truly intend to be accurate but accidentally get some information wrong, that’s an honest mistake. Ideally though, we present information, ourselves, and our motives without exaggeration, downplaying, or deceit, even if sharing the truth comes at a personal cost. Let’s look at some examples of good, honest truthfulness:

Someone dents your car when you aren’t around and leaves a note so you can contact them about repairs.

An employee tells a boss about a problem with a product so it can be fixed before the product is sold to the public.

During the 2008 US presidential campaign, false rumors were being spread that then candidate Barack Obama wasn’t a citizen of the US. His opponent in the race, John McCain, faced a constituent who said she couldn’t trust Barack Obama because she heard he was “an Arab.” John McCain responded, “No ma’am. He’s a decent family man, citizen, that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues.”[2]

In all these examples, despite some negative consequences to themselves, people chose to value truth while acting with respect, responsibility, and compassion for others. That’s good, honest truth.

TOO LITTLE TRUTH

Moving to one extreme of the continuum, we have too little truth—when someone changes the facts, misrepresents the situation, manipulates, or intentionally withholds information, with a disregard for the harm it may cause. Even worse, they may deceive with the intent to cause harm. For example:

Someone dents your car when you aren’t around and leaves a note with a fake phone number so onlookers think they’re being honest, but you won’t be able to contact them about repairs.

An employee changes safety data to hide a product problem that ultimately harms consumers.

Despite evidence that confirms the truth, a politician continues to spread rumors and distort facts to manipulate supporters into doing things that will serve the politician’s purposes.

In each of these examples, not only did people act dishonestly by sacrificing truth, they also acted with disrespect, irresponsibility, or a lack of compassion for the people they impacted. That’s immoral lack of truth.

TOO MUCH TRUTH

On the other extreme of the continuum, we have too much truth. When someone says, “Why’s everyone so upset? I’m just saying what’s true,” they’ve either shared facts they shouldn’t have, or they could have told the truth more kindly. For example:

A mother, with vicious delight, tells her teenager, “You look ridiculous and you’ll never get the job dressed like that. And by the way your brother is smarter than you and I like him better.”

Rather than share data about a product problem with his boss, an employee goes straight to upper management, hoping to get his boss fired so he can take her job.

Someone reveals another person’s sexual orientation or gender in order to damage them in a community or to incite a threat against them.

In these examples the information shared may have been accurate, but the person telling the truth had malicious intent and they may have acted with cruelty or vengeance. Telling the whole, accurate truth can be wrong when it’s done for the wrong reasons, or in a way that’s disrespectful, irresponsible, or lacks compassion.

Navigating the gray areas

In our look at the blacks and whites of truth telling above, you may have noticed two important factors that help us decide where the lines are between right and wrong.

1) INTENT– Does the truth teller have good or bad intentions?

2) CONSEQUENCES– How does telling the whole truth affect our ability to treat others with respect, responsibility, and compassion?

The morality of truth telling is based on a balance between accuracy, intent, and consequences. The gray areas about how much truth to tell arise when we feel we have a good reason (intent) to sacrifice some truth (accuracy) in order to treat people with respect, responsibility, and compassion (consequences).

Hard truths

The gray area between good, honest truth and too much truth has to do with telling people facts they may not want to hear, facts that may hurt their feelings, and facts that conflict with what they’d like to believe. But there’s a time when telling a hard truth is the responsible thing to do. For example:

An employee is being held back because their coworkers find them abrasive. When they ask their boss why they keep getting passed over for promotions, should their boss tell them the truth they need to correct the issue?

Someone’s beloved sister, who is hopelessly tone deaf, is planning to quit a good job to pursue a career as a singer. Should a caring and compassionate sibling respectfully tell her the truth about her chances at success?

In this gray area, the person hearing the truth may not like the news (especially if it’s negative feedback.) But if they need the information to make informed decisions and to have a realistic view of themselves, the person who is denying them the truth, even when it’s done with good intentions, may be acting irresponsibly.

Of course, being responsible and telling hard truths doesn’t mean we should deliver the hard truth with cruel relish. It’s not necessary to inform an employee that their social skills have all the finesse of a curmudgeon, nor should one tease their sister that she sings like a dying cow. While these descriptions may be creatively accurate, there’s a respectful and compassionate way to deliver hard truths while softening the blow. And, telling hard truths is about being responsible, not about meddling where it’s none of your business. If a stranger walks up to a family in a restaurant and volunteers, “Nobody asked me, but your child is a spoiled brat who needs to learn some manners,” we may all be thinking it, and it may be undeniably accurate. But that doesn’t mean it’s our business (responsibility) to interfere.

Polite and skillful lies

Between good, honest truth and too little truth, is the gray area where we bend the truth, with good intentions, and minimal consequences. This is the land of white lies, negotiation tactics, and positive spin. The danger in this gray area is that there’s a point where we can stray too far from the truth and we may be doing it for the wrong reasons—we can cross a line into manipulation and deceit. How do we know where that line is? We need to look to intent and the consequences we cause to respect, responsibility, and compassion. Let’s use some scenarios to explore where the line is.

The Gift– A child tells their grandparent they like a present, even though they won’t use it, in order to show compassion for Grandma’s feelings. That’s a white lie. But, if the child tells Grandma they can’t use the gift because it arrived broken in the hopes that Grandma will send something else, that’s manipulation.

The Ill-fitting Shirt– On the way out the door to a dinner party, a husband asks his spouse if his shirt is too snug (which it is). His wife says, “I think that fit is in style right now.” That’s spin. But, if the wife intentionally buys her husband clothes that are too snug with the hope he’ll be encouraged to lose weight, that’s manipulation. And if not telling her husband the truth will cause him public humiliation, that’s a negative consequence that a responsible and compassionate wife would try to prevent.

The Deal– A sales person accurately describes a product and then tells the customer how eager other buyers are, hoping to prompt the customer to make a decision (even though there’s plenty of inventory.) The customer is making their decision based on accurate product data, with a push of urgency. That’s a negotiation tactic. But, if the salesperson intentionally over-inflates performance data or invents non-existent customers to steer the buyer’s decision based on falsehoods, that’s deceit.

In each situation we can see whether someone had good intentions that caused minimal consequences or we can see that they had ulterior motives which required them to trick someone in order to benefit themselves. If someone is tricking or manipulating someone else for their own gain, that usually means they’ve crossed the line into an immoral wrong.

The unintended consequences of white lies

The gray areas are gray because we come into them with good intentions, but even good intentions can have unintended negative consequences. When we hide or bend the truth, we’re making a decision about how much information someone should have. In his book, Lying, best-selling author Sam Harris proposes that while we may think we’re telling a white lie out of compassion, white lies can actually be disrespectful.

When we presume to lie for the benefit of others, we have decided that we are the best judges of how much they should understand about their own lives—about how they appear, their reputations, or their prospects in the world. … Unless someone is suicidal or otherwise on the brink, deciding how much he should know about himself seems the quintessence of arrogance. What attitude could be more disrespectful of those we care about?[3]

When we’re considering consequences, we need to keep in mind that the person we think we’re helping with a white lie might really have preferred the truth so that they would have a more realistic assessment of themselves. You may recall from chapter 5 that if we want to have self-respect, we need to take an honest look at ourselves, including the stuff we’re proud of and the stuff we’re not happy with, so we can choose how we want to live. White lies lead us to a false understanding of ourselves. They deny us information we need to control our own lives. And, they encourage us to live in an alternate reality—our own land of make-believe. If everyone else is living in reality, and we’re living in a land of make-believe, we look the fool.

A path forward

In this age when people debate what the truth even is, we as a society must agree that the truth is about accurate facts that exist in reality. Sometimes people won’t like the facts, and that’s why there are times, in order to cooperate and compete without harming each other, we present the truth in a way that also honors respect, responsibility, and compassion. We navigate the gray areas around truth telling so we can decide when there is a time to speak up and a time to stay silent; when there is a time for the hard truth and a time for a softer, more polite version of the truth. But at the end of the day, we need the truth. We’ll see in the next two chapters that the truth is essential to our well-being as individuals and as a society. Without it, we don’t have a shared reality.

Excerpt reprinted from the book Rooted in Decency with the author's permission. © 2022 Colleen Doyle Bryant.

Buy the Book

Journaling

Explore your thoughts with these journaling prompts:

- Were any of the virtues and behaviors included in truthfulness surprising to you? (For example, sincerity and trustworthiness or not rationalizing or being hypocritical.)

- Have you ever been told a white lie but wish you’d been told the truth? Why?

- Are there any truths or lies you’ve told where you might need to rethink whether it was the right thing to do?

Want to read more?

Buy the print or ebook and start your journey.

Sources

Endnotes- Chapter 14: What is Truth?

1. Sources for definition and discussion of degrees of truth:

- My experience writing books and teaching resources on honesty: see Bryant, n.d.-a in the references list.

- The world belief systems in chapter 12 of this book, Rooted in decency.

- General sources on truth:

Robert Feldman, The liar in your life: The way to truthful relationships (Twelve 2009).

Sam Harris, Lying (Four Elephants Press 2013).

Lee McIntyre, Post-truth (MIT Press 2018).

Pamela Meyer, Liespotting: Proven techniques to detect deception (St. Martin’s Press 2010).

2. Danny Clemens, ‘He’s a decent family man’: Watch the moment John McCain defended Barack Obama on 2008 campaign trail, ABC7 Chicago, 2018, August 26.

3. Sam Harris, Lying, p. 13, Emphasis from original source.

Note: This page contains affiliate links.