Chapter 8

Us Versus Them

How group identity isn't the real problem

Sometime in the distant future, two friends discuss the government’s call for unity.

Ash: You want me to just forget about all the times they treated me like I wasn’t one of them? Like I wasn’t the right race or religion or gender or nationality or political party?

Forrest: Yesterday there weren’t aliens hovering in the sky trying to colonize us Earthlings. Today, none of those differences matter. Today, we’re united as humans.

Ash: A galactic common enemy? That’s what it took?

We saw in the last chapter that we like to be aligned with others in our group, but those bonds that we cherish may also limit our ability to see points of view outside our own sphere. In this world gone sideways, it can feel like group loyalty is the source of a lot of our problems, as divisiveness breaks us into competing factions.

Yet we saw in chapter 6 that group life is a good thing. Group unity is what would give us a fighting chance if we really were staring at a sky teeming with alien marauders. But forming groups isn’t just about defeating a foe, it’s also about feeling camaraderie, cooperating toward shared goals, and finding purpose and strength in the face of life’s challenges. So group orientation in general can’t be the problem. There must be something in the way we’re going about group life in today’s times that is creating this divisive atmosphere.

The biology and allure of group identity

To understand the power of group identity, we need to take a short side trip into biology. In Behave: The Biology of Humans at our Best and Worst, neurology researcher Robert Sapolsky explains that without even thinking about it, we constantly look for group markers and we’ll sort ourselves based on anything we find in common.[1] Interestingly, we don’t restrict ourselves to “big” categories like race, religion, or political affiliation. We can unite on any number of factors, like our favorite sports team, the company we work for, our favorite brand, the age of our children, and whether we think Superman is cooler than Batman (He totally is.)

The great thing about this, is that we can quickly shift our group orientation based on a different aspect of ourselves. For example, in one moment we’re focused on being a loyal company employee in a competitive negotiation, but that can change the moment we discover the person we’re negotiating with is a loyal fan of an underdog sports team, just like we are. Go team! Let’s make this deal happen.

We also see this more poignantly when people from different backgrounds instantly come together as rescuers to help a stranger in distress. We’re not locked-in to any one group, or even to learned social biases. All we need is a common goal, a common enemy, or another common characteristic to render other biases unimportant in the moment.

My group’s better than yours

Given how important group life has been to our survival, it’s not surprising that our brains have adapted to identify Us and Them, and to quickly form bonds that favor “Us.” A brain chemical called oxytocin helps people feel more caring, trusting, and empathetic toward each other while mirror neurons in our brains help us to feel each other’s joy, pain, fear, and excitement. But when we’re with group members, the effects of oxytocin and mirroring are amplified. They influence us to care, trust, and empathize even more with in-group members so we can cooperate more quickly and form stronger attachments to get us through challenges.[2] Remember the aliens in the opening dialog? Standing side-by-side on Earth against a common enemy, we would feel each other’s emotions and oxytocin would help us trust each other and care what happens to each other.

No matter how we define the “common ground” we quickly develop a rosier picture of what it is to be one of “Us.” A great example of this is the study of the reds and the blues, where preschoolers were put in either red or blue t-shirts for a few weeks. In the best-selling book NurtureShock: New Thinking about Children, the authors describe how, without the influence of any value judgments from their teachers, the children quickly developed bias for other kids who wore the same color t-shirt they did. Within weeks, the children didn’t show hatred toward the kids in a different color t-shirt, but when asked about the groups, the preschoolers answered that those in the same color t-shirt—the Us-es—were better and nicer. They said that some of the children in the other color t-shirt—the Thems—were “mean, and some were dumb,” but none of the Us-es were.[3]

Just like those preschoolers, we adults inflate our perception of the core values of someone we perceive as an Us. Sapolsky explains, in Behave, that we assume that our in-group is more “correct, wise, moral and worthy.”[4] We act more trusting, generous, and cooperative with in-group members while we view Thems as more “threatening, angry, and untrustworthy.”[5] Remember though, often these judgments aren’t based on any meaningful measure. The color t-shirt a child wears doesn’t have anything to do with how trustworthy and wise they are. We develop bias toward an Us simply because they’re an Us and we develop bias against a Them simply because they’re a Them.

Making it a moral issue

Focusing on who is better, more trustworthy, or more deserving of empathy and respect—that means we’re into moral territory because we’re judging based on virtues like trustworthiness and respect. Now let’s bring the brain back into it. When we see a Them as morally offensive, the same part of our brain activates as when we’re smelling rancid food.[6] Yes, you read that right. It’s called the gustatory response, and it’s that automatic sense of disgust that pulls us back and away in order to protect us from things that would cause us harm, like eating spoiled food or picking up germs from garbage. Moral disgust toward a Them affects our brain in the same way as things that cause physical disgust. Neurology researcher Sapolsky explains:

The insula activates when we eat a cockroach or imagine doing so. And the insula and amygdala activate when we think of the neighboring tribe as loathsome cockroaches. As we’ll see, this is central to how our brains process “us and them.”[7]

He goes on to note that the amount the brain is activated for moral disgust toward a Them “predicts how much outrage you feel and how much revenge you take.”[8] This biological response reinforces our sense that Thems whom we feel morally offended by are an actual threat to our well-being, just like rancid food would be, even if there’s no real-world evidence to support it.

Leveraging the sense of moral disgust

So what do you suppose would happen if our sense of moral disgust was constantly activated against Thems? Well, we’re seeing the effects of moral disgust in our political divisiveness today. One of the ways we got to the state we’re in was by normalizing extreme behavior in politics, including the use of extreme words that light up our moral disgust response. As historian Julian Zelizer explains in Burning Down the House:

An entire generation of Democrats and Republicans came of professional age watching a brutal style of political warfare in the 1980s and 1990s that spared nobody. The kinds of political fights that were once associated with the extreme fringes of democracy entered the mainstream, where they would stay.[9]

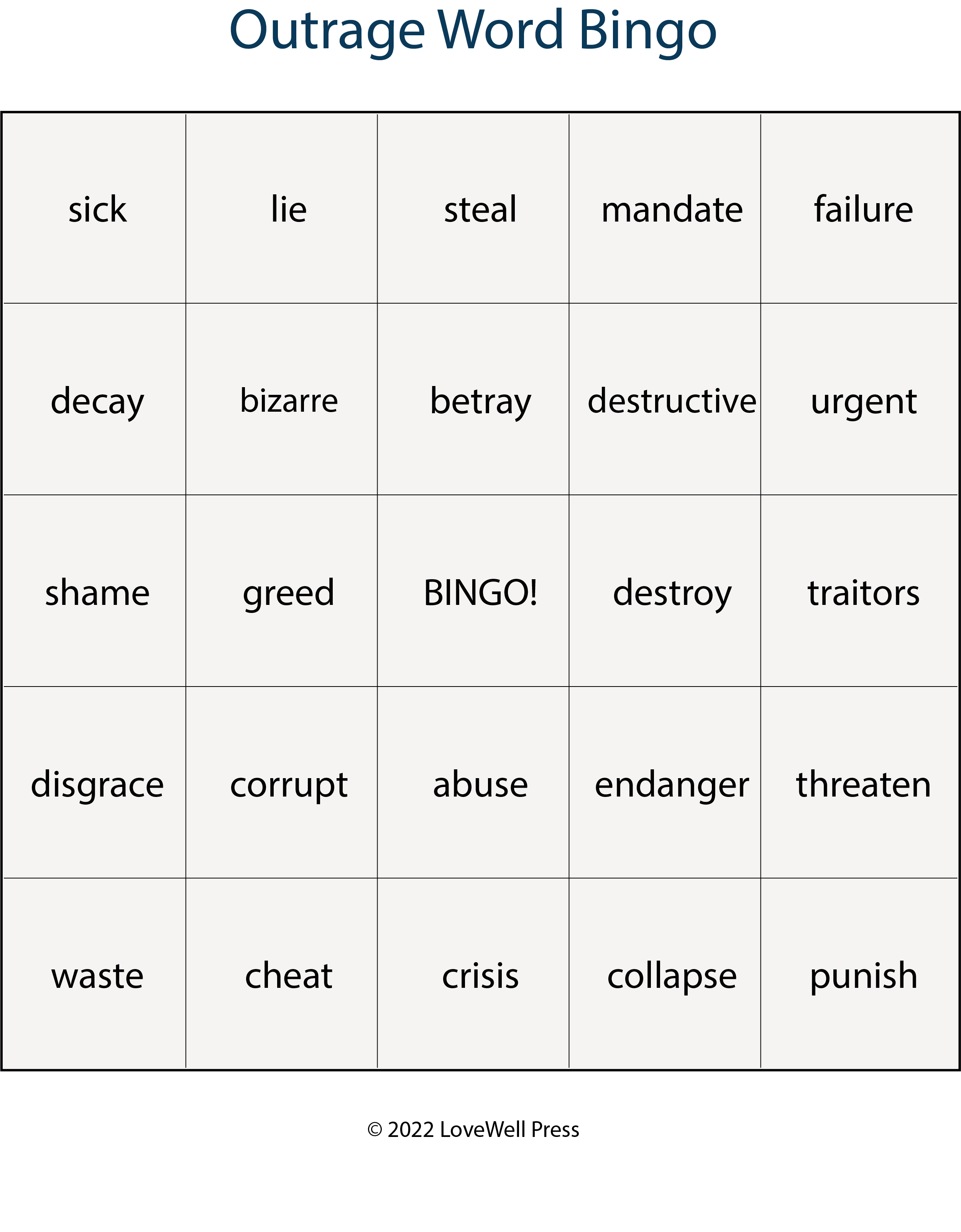

One example of that escalation is a memo released in 1990 titled, “Language: A Key Mechanism of Control.”[10] Inspired by politician Newt Gingrich’s speaking style, the memo was distributed by GOPAC, an organization that develops Republican leaders. The memo advised: “The words and phrases are powerful.”; “Remember that creating a difference helps you.”; “Apply these to the opponent, their record, proposals and their party.” The words to be used against the other party included:

Words that activate moral disgust, such as “decay”, “sick”, “waste”, “disgrace”, “shame”, “betray”, “traitors”

Words that represent immoral behavior, such as “lie”, “hypocrisy”, “greed”, “corrupt”, “cheat”, “steal”

Words that create a sense of being under threat, such as “collapsing”, “crisis”, “destructive”, “destroy”, “endanger”, “devour”

During this political era, words and behaviors that were so outside the norm that they had been viewed as dangerous—they became the new normal. I’m not blaming any one group—there’s plenty of responsibility to go around. Zelizer, in Burning Down the House, and conservative commentator Charles Sykes, in How the Right Lost Its Mind, each offer detailed accounts of actions by multiple players—Democrats, Republicans, the media, talk radio, social media, and the public’s willing embrace of divisive drama—that led to the state we’re in.[11] Zelizer explains, “Although politics was always rough in America… the overall level of respect for elected officials and governance rapidly diminished as a result of this era in congressional history.”[12] Part of what changed is that the tone of the debate between Us and Them took on attributes of moral disgust, feeding the idea that we’re in a battle against something that can harm us.

Feeding a tribal battle for survival

Consider some of the different ways politicians, pundits, and regular people alike talk about a new policy:

Stating Facts: “Here’s the new policy and here’s how it may impact society, based on evidence.”

Delivering Disgust: “They should be ashamed of this new policy. What they’re doing is sick.“

Inciting Outrage: “This policy is a betrayal and it threatens to destroy us.”

As the intensity increases toward inciting outrage, the language motivates people—and it drives clicks and viewership. So we can understand why so many panels, consultants, experts, activists, and anchors choose to go down this path.

We can see an example of this in the debate around Florida’s Parental Rights in Education law, a measure forbidding instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity in kindergarten through third grade.[13] When critics, including the LGBTQ community, opposed the bill they called the “Don’t Say Gay” law, some conservative commentators inaccurately started talking about the law using the word “grooming,” a word associated with child sexual abuse, which is an act that incites tremendous moral disgust on all sides of politics. One far-right commentator, reflecting the cognitive distortions we saw in chapter 2, amplified the false association, stating that anyone who opposes any bills like this one is “pro-child predator.”[14] The issue became more divisive as moral disgust overwhelmed rational discussion. As neuroscience showed us a few paragraphs ago, the more moral disgust is activated, the stronger the negative response, the greater the sense of threat, and the more potential that those who feel threatened will have a desire for revenge.

The issue with Us and Them isn’t that they exist; the sense of community we gain from being an Us has clear benefits as we saw in chapter 6. The issue with Us and Them appears when we emphasize our differences to the point that they feed a tribal battle for survival. David Brooks, in The Second Mountain, describes the situation:

Community is connection based on mutual affection. Tribalism, in the sense I’m using it here, is connection based on mutual hatred. Community is based on common humanity; tribalism on common foe. Tribalism is always erecting boundaries and creating friend/enemy distinctions. The tribal mentality is a warrior mentality based on scarcity.[15]

Reestablishing objectivity

So what can we to do about it? How do we dial back the moral disgust that feeds outrage and divides us so that we can move back toward cooperation?

Four Effective Ways to Diminish Divisiveness

1. Recognize our biases

First, remember that we’re biologically driven to be biased toward our in-group. Knowing this, we can choose to turn on a mental Check Accuracy Warning Light that alerts us to the possibility that we’re thinking automatically about Us and Them. Remember chapter 2, where we compared mindless (automatic) thinking to mindful (executive brain) thinking? When we pay attention to our Check Accuracy Warning, we can engage mindful thinking, bringing reason and evidence back into the picture; and we can reap the benefits of greater accuracy, competence, and adaptability. Being aware of our biases may help us see that the out-group isn’t as awful as our emotional reactions tell us they are. And maybe, that the in-group isn’t as trustworthy and without fault as we’d like to think it is.

2. Raise our awareness of the use of outrage

Some people, groups, businesses, and politicians benefit from stoking outrage. Whether they’re choosing words that activate moral disgust intentionally or not, we can recognize when they’re doing it. So wherever you get your information, play a game I call Outrage Word Bingo, noting how often words that stoke outrage are being used. This will help shed light on whether you’re hearing facts, opinions, or provocations. You can question the validity of extreme statements and demand more balanced language by choosing where you tune in, how you click, and how you vote. If a manufacturer was producing their product in a way that caused harm to society, we would object. We wouldn’t buy it. We don’t have to buy the outrage people are selling either.

3. Bring balance to extreme thinking

It’s worth noting that during the 1990s while divisive words and tactics increased in politics, political moderates were stepping out of participating in political communities at greater numbers than those with “very liberal” or “very conservative” views. In 2000, Robert Putnam wrote in Bowling Alone:

Ironically, more and more Americans describe their political views as middle of the road or moderate, but the more polarized extremes on the ideological spectrum account for a bigger and bigger share of those who attend meetings, write letters, serve on committees, and so on. The more extreme views have gradually become more dominant in grassroots American civic life as more moderate voices have fallen silent.[16]

Another way to bring more balance to political discussions is for moderates to ensure their views are being heard alongside more liberal and conservative views in public meetings, local organizations, political parties, rallies, and other forms of civic life.

4. Emphasize our similarities

We’ve seen that we don’t have to be locked-in to any single group identity. In fact, we’re able to quickly shift our group loyalties simply by changing our perspective and finding something we have in common to rally around. In part three of this book, we’ll see that we still have shared values. And we can rally together as decent humans, looking for reasonable and responsible solutions so we can live well together. Instead of emphasizing the differences that separate Us and Them, we can find the common ground that helps all of us work toward a shared goal, and that can help us get through a divisive time without damaging each other.

A path forward

Biology plays a powerful role in helping us bond with others to survive and to thrive, but it also can blind us to a complete perspective. When we question our assumptions, we give ourselves the chance to see a more accurate picture of reality, and we give ourselves the choice not to be fed outrage for someone else’s gain. All of us—Us and Them—can take an active role in reintroducing balancing views to the public dialog and we can find new common bonds that have the power to override old divisions that don’t serve us.

Excerpt reprinted from the book Rooted in Decency with the author's permission. © 2022 Colleen Doyle Bryant.

Buy the Book

Journaling

Explore your thoughts with these journaling prompts:

- When is a time you saw people come together quickly? Did they do so by finding a common goal, a common enemy, or a common characteristic?

- What are some assumptions you make about people in your group—your Us-es? How about your assumptions about Thems?

- What is something you would like to do differently, this week, based on what you learned in this chapter?

Play Outrage Word Bingo

Want to read more?

Buy the print or ebook and start your journey.

Sources

Endnotes- Chapter 8: Us Vs. Them

1. Robert Sapolsky, Behave: The biology of humans at our best and worst (Penguin 2017).

2. Discussion of oxytocin and mirror neurons from Robert Sapolsky, Behave (Penguin 2017) and Jonathan Haidt, The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion (Pantheon Books 2012).

3. Po Bronson & Ashley Merryman, NurtureShock: New thinking about children (Twelve 2009), Kindle loc: 737.

5. _____, p. 398.

6. Supported by Sapolsky, Behave, and Haidt, The righteous mind.

8. _____, p.41.

9. Julian Zelizer, Burning down the house: Newt Gingrich, and the rise of the new Republican party (Penguin 2020), p. 302.

10. GOPAC Memo, 1990, “Language a Key Mechanism of Control”, original document shown in the Internet Archive. Article clarifying publication date: Michael Oreskes, “For G.O.P. Arsenal, 133 Words to Fire”, New York Times, 1990, September 9.

11. See Zelizer, Burning down the House, and Charles Sykes, How the right lost its mind (St. Martin's 2017).

12. Julian Zelizer, Burning down the house, pp. 302-303.

13. NPR, What Florida’s parental rights in education law means for teachers, 2022, April 5.

14. Emily Brooks, ‘Groomer’ debate inflames GOP fight over Florida law, The Hill, 2022, April 8.

15. David Brooks, The second mountain: The quest for a moral life (Penguin 2019), p. 35.

16. Robert Putnam, Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community (Revised and updated) (Simon & Schuster 2020), p. 342.

Note: This page contains affiliate links.