We’ve been watching an escalation of political violence and plenty of people are looking for someone to blame. Do you find yourself wondering though, how did it come to this? Why are people acting so disrespectfully, dishonestly, and now aggressively? We Americans have a long history of disagreeing without turning to violence. So, why are incidents of political violence happening so often now?

We can find some answers by looking back about thirty years, to a time when the tone of how we talk about politics changed and we started using words that activate our sense of moral disgust—a biological reaction that helps protect us from danger. Layer on top of that the cultural shift toward public shaming—which prompts a psychological response to defend ourselves—and we’ve created a culture in which people are living in a constant state of fear and self-defense.

The words we use with each other may seem like mere rhetoric, but there are biological and psychological forces at play that may be encouraging people to suspend their usual moral codes and to justify immoral actions due to a false sense that they are acting in self-defense.

Changing the Rules of Engagement

Before we get into the biology and psychology of what’s happening with divisiveness today, let’s take a quick sidestep to see why self-defense may be a factor in people committing extreme, and often immoral acts, against their political opponents today.

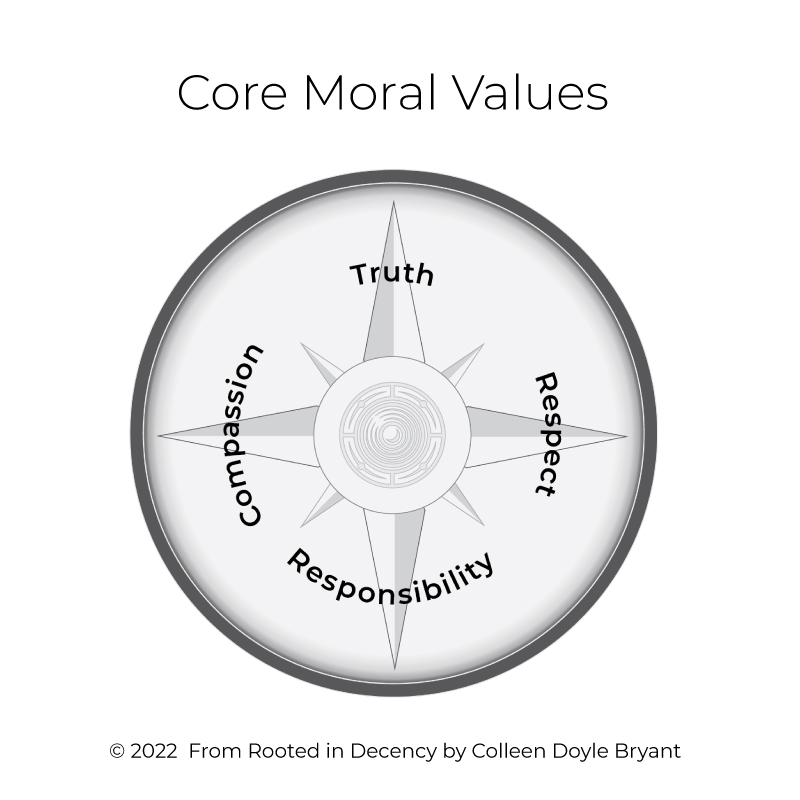

Based on core human morality, is it ok to kill another human? The answer is usually, "No!" But what if someone commits violence in self-defense? Next, let's consider truth. Is it ok to lie? What if someone lies in order to save another person's life? These two examples show us that there are times people feel justified, and even obligated, to violate normal moral standards. Acting in self-defense, including protecting our families or way of life, can change how people perceive what’s right and wrong. People who feel they are under attack may enact new rules of engagement that suspend the honesty, respect, responsibility, and compassion that are the foundation of human societies.

What we’ll see in the coming paragraphs is that the use of moral disgust and public shaming are feeding the sense that people are under attack, which may be causing some people to suspend their normal moral standards, allowing them to justify immoral choices, under a false sense that they are acting out of self-defense.

The Power of Moral Disgust

First, let's start by looking at moral disgust. Today, instead of talking about policy and how it may help or harm people, opponents often speak solely in attacks about why the other side is not only wrong, but that they're morally disgusting for what they believe. We may think talking about being disgusted with someone is just expressing a thought about them, but in reality moral disgust is far more powerful than that. When we use words to describe people that convey moral disgust, it sets in motion a powerful mental and physical reaction that prompts people to protect theselves from a potential danger.

Let’s do a quick experiment to see the effect moral disgust has on us. As you read the next scenario, pay attention to what happens in your body.

Imagine that someone takes a package of meat out of the fridge that’s well past its sell by date—it’s in the brownish-gray stage. They wave it under your nose and ask, “Does this smell bad to you?”

As you imagined that stench reaching your nose, what did your body do? In all likelihood, you pulled back and away because your body has an automatic gustatory response that helps protect you from things like rotten food that can cause you harm. That same part of our brain reacts when we think a person is morally disgusting. Neurology researcher Robert Sapolsky, in his book Behave, explains it like this:

The insula activates when we eat a cockroach or imagine doing so. And the insula and amygdala activate when we think of the neighboring tribe as loathsome cockroaches. As we’ll see, this is central to how our brains process “us and them."

In this age when we’re deeply divided into groups of Us and Them, moral disgust may prompt us to see political opponents as an actual threat to our well-being, just like rancid food would be. But reaching the divisive state we’re in didn’t happen overnight. We’ve actually been stewing in this culture for about thirty years now, unaware of how we’ve been affecting each other with our word choice.

Flashback to the Beginning of The Age of Moral Disgust

In the 1990s, a new style of speaking emerged that encouraged politicians to use specific words that motivated people. What people likely didn’t realize at the time is that the words they were using to inspire their followers were casting their opponents as morally disgusting, and they were laying a foundation for today’s pervasive moral battles. What kind of words are we talking about that create a state of moral disgust? Here are some words taken from a memo that trained politicians how to speak in the 1990s.

Words that activate moral disgust: “decay”, “sick”, “waste”, “disgrace”, “shame”, “betray”, “traitors”

Words that represent immoral behavior: “lie”, “hypocrisy”, “greed”, “corrupt”, “cheat”, “steal”

Words that create a sense of being under threat: “collapsing”, “crisis”, “destructive”, “destroy”, “endanger”, “devour”

Today, it doesn't matter who started using words of disgust because they're now used on both sides of the aisle, by the media, in podcasts, and even in our general way of speaking with each other. After thirty years, they’ve become so pervasive, we may not realize that, according to historian Julian Zelizer, before the 1990s, using words like this in politics was considered to be dangerous and far outside the norm. Today, it’s our new normal. Arguments often take an all-or-nothing tone on why the other side is sick or a disgrace, how they’re betraying our nation’s principles, and how they’re destroying our country.

One reason political divisiveness is so deeply entrenched today is that we’ve spent several decades being shaped by a culture that can urge us to feel that those who have a different political opinion are an actual threat to our well-being. Why are people more rude, aggressive, and even violent today? One reason may be found in Sapolsky’s Behave where he explains that the amount the brain is activated for moral disgust toward a Them “predicts how much outrage you feel and how much revenge you take.”

Shaming People into Agreement

A second dimension driving aggression today comes from the widespread use of shame. A recent Google search returned over 100,000 news articles in which someone "should be ashamed of" themselves. Shame culture, including cancel culture and call out culture, are extensions of this age of moral disgust, where people are presenting issues in terms of absolute right and wrong, with a moral imperative that their way is not only the best way, it’s the only right way.

If we assume good intent, people who are casting shame upon others may mean to say, “You’re doing something that’s wrong and harmful and you should change your ways.” But that’s not how shame works. Shame is not a criticism of a what someone did, it’s a criticism of who they are. It’s right there in the words, “You should be ashamed of yourSELF.” One of our fundamental goals in life is to create a positive sense of our self, so having the entirety of our being attacked can cause a strong psychological reaction.

Researchers explain that shame interrupts empathy, and instead of considering how their actions may have caused harm, people being shamed tend to withdraw, deny, become defensive, or turn angry. Shaming is a way of casting someone out, declaring that something is wrong with them and they aren’t fit for society. It feels threatening because it is— a social creature who is cast out of society is a vulnerable creature.

When we see conservatives aligning together saying they feel their way of life is being threatened or when we see liberals rallying together saying that their right to exist is being denied, it may well be a reaction to a culture of shaming that declares not that something is wrong with what they’ve done, but that something is wrong with who they are.

The bottom line with shame is that you can’t shame someone into agreeing with you. Rather than create an empathetic response that might lead someone to change their behavior, shaming creates a sense of threat that turns the accused toward others who will support them in the very behavior the accuser is trying to stop. And all the while, it adds to this climate of fear and threat, where some people may feel they are defending their very right to live with freedom and dignity.

How to move forward toward cooperation and shared values

Talking about our political opponents in terms of moral disgust and shame is far more negative and powerful than most of us likely realize because it can make people feel like they are under attack and need to protect themselves. When we position so many of our political issues as if we have a moral imperative, we’re fueling a climate that may allow and even encourage people to put aside core moral values in the name of self-defense.

Let’s be clear— acting out in violence because of a false or inflated sense of self-defense is morally wrong. But if we’re asking ourselves how we can prevent political violence, and how we can heal divisiveness, we need to recognize the role that moral disgust and shaming play in creating a climate of threat.

One step we can take right now to help us move forward out of this constant sense of threat, is to put down our verbal weapons. Individually we can choose to talk about our political opponents with more respect, avoiding words that activate moral disgust and shame. Psychology researchers have found that when we stick to facts, showing actions and consequences without the shame, people are more likely to respond with empathy and to want to correct any harm that‘s being done. That may not be easy when there’s such a long history of hurt and anger. But in any conflict, we need to ask ourselves what we really want, and whether what we’re doing is actually helping us get there. We have plenty of proof that the way we’re communicating now will only drive us further into separation, defensiveness, and increasing levels of violence. If what we really want is to move forward past this culture of incivility, we each need to recommit to shared human values and common decency.

You can read more about Moral Disgust in this free chapter online: Chapter 8: Us vs Them from the book, Rooted in Decency. For more on shame culture, see chapter 18: Working Against Ourselves, Why you can’t disrespect someone into agreeing with you, available in print or ebook. Full citations for the works referenced here are available in those chapters.

Note, this page includes affiliate links.