Chapter 17

What is Respect?

How too little and too much respect are destabilizing society

Let’s take our moral compass back out of our pocket and check our bearings. We just explored TRUTH, so now let’s change course to explore RESPECT. Ask any American about the state of respect in our culture today and you’ll likely get an earful—“Social media is poison!”; “Politics is malignant!”; “Kids these days!” Okay, every generation since the beginning of time has said that last one. The point is, disrespect is everywhere and it’s part of the reason we’re feeling like the world has gone sideways, wondering what happened to people and what happened to society. So let’s get to know RESPECT, and see how both too little respect—and too much respect—are putting our sense of stability off-balance.

Defining respect

What is Respect?

When we respect someone or something, we treat it with appropriate care because we feel there is a good reason to do so.

We talk about respect in different flavors, for instance: we treat someone with respect, we have respect for a person, we respect the law. On the surface, it seems like respect has several different meanings around courtesy, admiration, and deference. But underneath, there’s a common thread that reveals the true meaning of respect, and it’s tied to the fact that we don’t respect just anything. Respect requires a reason—we’re acknowledging something is worth paying attention to and worth altering our actions for. 1 When we use it as a verb, RESPECT is to take appropriate care with someone or something, because we feel it’s important to do so.2

To treat someone with respect means we act courteously because we feel the person or the situation warrants it.

To have respect for someone means we admire them because they’ve done something worthy of our esteem.

To show respect for the law means we follow the rules because we recognize the importance of order in society.

We can see two components in each of these examples.

1) The way we treat someone/something (with courtesy, admiration, deference)

2) The reason we do it (because we feel it’s worth our effort)

You might want to sit up for a second because these two little insights are a big deal.

When you act with respect, you are choosing how you act in order to preserve something you value. Respect isn’t simply about being polite or showing admiration; it’s about acknowledging the things you value and acting in a way that honors their worth. Thinking of respect from this perspective helps human behavior make more sense:

Why treat a stranger we’ll never meet again with respectful courtesy? We don’t admire the person; we don’t even know them. But we do recognize their value as a fellow human, and we recognize the value of maintaining a civilized society.

Why respect someone’s freedom to express an opinion you don’t agree with? Because we value the freedom to have an opinion—to have control over our own minds. And we value the importance of dialog in a society where we need to find peace between diverse views.

Why treat enemy combatants with a degree of respect? Wow, that seems like an abrupt shift! Stay with it for a second, because this example shows how we even have guiding principles of respect for our wartime enemies—people we don’t agree with, who have tried to do us harm. Why do we ban abuse and degrading treatment even in war? Because at the heart of respect is our value for human life and dignity.

What these situations show us is that when we treat someone or something with respect, it isn’t necessarily because we admire the person or the thing receiving the good treatment, but we do value the principle that people and things have worth and should be treated with appropriate care and dignity.

Respect as a common value

Respect plays a prominent role in the world’s belief systems that we saw in chapter 12. It’s woven throughout the teachings not just in specific behaviors, but as an overarching theme that each person should treat others with care. In terms of specific behaviors, the belief systems weave respect throughout human interaction:

Respect for human life– We see this in guidance on not killing, non-violence, and taking action to protect the dignity and well-being of all people, particularly the vulnerable.

Self-respect with humility– The belief systems emphasize that each human should know their own worth but should live without arrogance and selfishness, being aware of their impact on others.

Respect through fairness and justice– All of the systems emphasize that each person should get the rewards they earn as well as suffer the consequences they bring upon themselves. We are personally responsible for the ways we impact others.

Respect in relationships– The expectation that each person should treat others with respect and work toward fairness and reciprocity appears in guidelines about:

- Behavior– treating others with courtesy, graciousness, and benevolence

- Sexuality– respecting commitments and well-being

- Family– honoring elders, caring for those who cared for you

- Property rights– not taking what belongs to others

- Business practices– prohibitions on exploitation and cheating

Finally, all the belief systems emphasize the need for balance and temperance, which is to say respecting boundaries and respecting the demands of morality.

Why respect is important

We saw in chapter 11 that moral values grew out of a need for ground rules that helped humans establish the trust, fairness, and reciprocity people needed to cooperate and flourish together. It’s no surprise then that the world belief systems all included a version of the ultimate ground rule, a.k.a The Golden Rule—to treat people the way you’d like to be treated. The Golden Rule is fair. It supports reciprocity. It invites trust. Communal life is possible when we share an unspoken agreement to treat each other and our principles with the respect we’d like in return:

I’ll treat you with the care and dignity that you deserve, and in return, I expect that you’ll treat me with the care and dignity that I deserve. —That’s reciprocal respect for people.

I’ll honor the ground rules that govern peaceful, cooperative existence, and in return, I expect you to do the same. —That’s reciprocal respect for principles, law, and order.

We’ll each come into this arrangement of mutual respect with our human dignity, and over time we’ll each get what we deserve based on the way we choose to live our lives. —That’s fairness and justice.

Respect, which is treating people and things with care to preserve something we value (like civil society, law and order, fairness, and justice) is at the core of our ability to live peacefully and productively together.

Respect, fairness and justice in modern democracy

Fast forward more than a thousand years and we see how these ideas continue to drive a modern democratic society. John Rawls, arguably the most important political philosopher of the 20th century,3 states in Justice as Fairness, that we function as a society by recognizing and following shared principles that guide fair cooperation:

Reasonable persons … understand that they are to honor these principles, even at the expense of their own interests as circumstances may require, provided others likewise may be expected to honor them. It is unreasonable … not to honor fair terms of cooperation that others may reasonably be expected to accept; it is worse than unreasonable if one merely seems, or pretends, to propose or honor them but is ready to violate them to one’s advantage as the occasion permits.4

Respect is one of those essential ground rules for reasonable people who want to manage life among other reasonable people. Rawls explains that it may serve rational self-interest to take advantage of others or to ignore the rules for your own gain. But in terms of being part of society, it’s not reasonable, and “common sense views the reasonable but not, in general, the rational, as a moral idea.”5 In plainer words, just because you can, doesn’t mean you should.

We’ve been talking about why life seems off-kilter. People who act unreasonably throw a society off balance. A culture of disrespect, where we can’t expect people to treat each other or our governing principles with dignity, care, and fairness, is fundamentally unsettling—it destabilizes the rules of engagement. Respect is a promise given and an expectation of return that enables us to trust and cooperate with each other in a stable, predictable, and just way.

The Respect Continuum

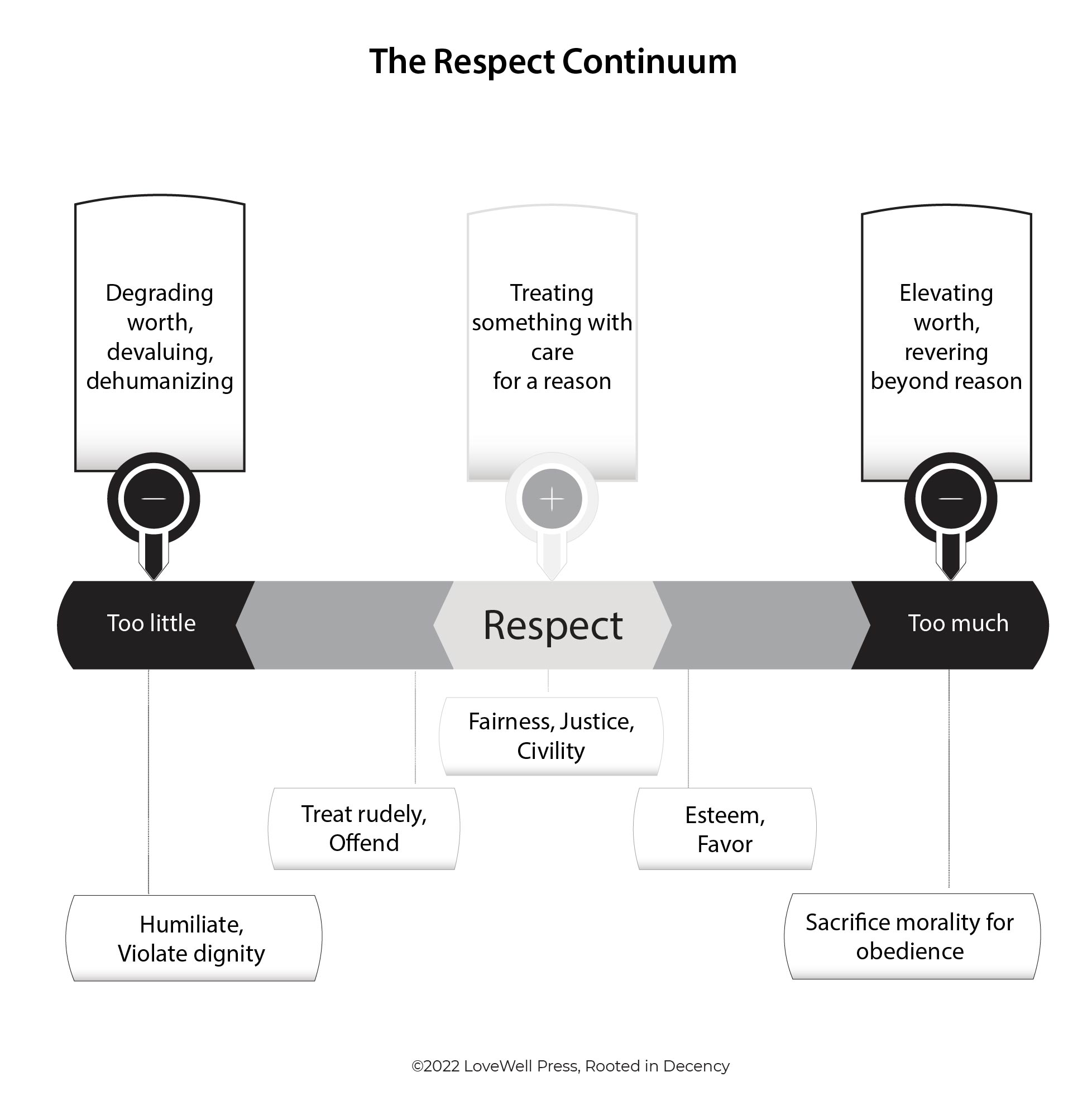

Now that we’ve established respect is so much more than being polite or admiring people, let’s take a closer look at the degrees of respect. Like we did for TRUTH in chapter 14, let’s put RESPECT on a continuum, from too little respect to too much respect, with a range of blacks, whites, and grays that show degrees of moral right and wrong. The Respect Continuum will show us that a lack of respect isn’t just about insults. Importantly, and perhaps surprisingly, it will show us that too much respect can lead us to blindly sacrifice our own moral principles.

GOOD, MORAL RESPECT

Starting at the middle of the continuum, we have good, moral respect, where we acknowledge the value of someone or something and act in a way that preserves its value. Let’s look at some examples of respect in real life:

Throughout our day, we treat people with the courtesy and dignity we’d like in return.

When people disagree with each other, they focus on the reasons why and don’t launch into demeaning personal attacks.

If someone’s group wants to do something they would consider degrading if it were being done to them, at a minimum, the group member doesn’t participate. Ideally, they would show courage to stand up for what’s respectful, even to opponents.

Respect in the middle of the continuum comes from a neutral state where we remember what we value—such as dignity, civility, fairness, and our other moral principles—and we act in a way that protects and preserves them.

TOO LITTLE RESPECT

One side of the continuum, toward too little respect, is about devaluing a person, principle, or thing. In mild forms this causes minimal damage, like when someone is insulting to another person. As we saw with TRUTH, in morality, intent matters. There’s a difference between:

1) someone unintentionally causing offense, and

2) someone intentionally being degrading.

For example, accidentally calling someone by the wrong name is more rude than immoral, while intentionally calling someone by the wrong name may be meant to degrade them.

If we flashback to chapter 2 where we talked about how cognitive distortions (like catastrophizing and labeling) are leading people to exaggerate or downplay harm, we may need to more carefully consider how we’re assessing degrees of disrespect today.

When we treat an accidental or mild offense as if it’s as bad as an act that demeans or humiliates—or on the other hand when we treat degrading behavior as if it’s no big deal—that distorts our ability to fairly assess disrespect.

We need degrees by which we can accurately judge the gray areas. When everything is pronounced a catastrophe, it feels like nothing is that bad. When everything is dismissed, it feels like nothing is being acknowledged. We need balance in all our moral principles, including accuracy about the severity of disrespect, and compassion for those who cause unintended offense.

As we move even further on the continuum toward too little respect, the value of something can be dismissed completely. With people, this is the act of dehumanizing—stripping people of their worth and dignity. Renowned moral philosopher Jonathan Glover, in Humanity: A Moral History of the Twentieth Century, examines how people were able to behave with such cruelty and violence toward each other in recent history. He found that humans are able to suspend their morality and stop their natural aversion to cruelty, in part, by dehumanizing their victims. Regular people were able to violate, torture, and kill because they stopped seeing their opponents as people. A lack of respect for our principles around dignity, fairness, and compassion can lead to the guiding light of our humanity being extinguished.

TOO MUCH RESPECT

To the other side of the respect continuum, too much respect, we elevate the value of something. In healthy, moral forms, we acknowledge that someone or something is worthy of our admiration and we treat them with extra appreciation, like people who persevere despite challenges or people who accomplish something extraordinary. When we’re compelled to respect someone for their moral goodness, kindness, or compassion, our bodies help us recognize it with a “warm, uplifting” feeling that social scientist Jonathan Haidt says “makes a person want to help others and to become a better person.”6 These are all examples of a positive state of respect, where we raise the value of something that deserves it.

Further down the continuum though, too much respect can morph into something more dangerous, where we elevate a person or an idea until we judge it as having supreme moral value. We may follow a person or commit to a cause and then give ourselves permission to sacrifice moral principles to protect it. For example:

In the free speech debate on college campuses, students have protested speakers whose views, they feel, may be offensive to some students (such as the examples we saw in chapter 2.) The protesters are coming from a place of good intent to respect certain groups of people. But they’re doing it by devaluing the rights of others—limiting free speech and preventing the dialog that’s necessary to maintain peace in a society with diverse views. To protect dignity and justice for some people, students have shouted down speakers with demeaning and unjust accusations.7 In the name of preventing the “violence” of hearing views they perceive to be demeaning, they’ve used physical violence and humiliated others.

Aside from the obvious hypocrisy, degrading one group as a method to protect the dignity of another violates principles of respect and compassion. A similar example can be seen in the January 6 attacks on the US Capitol Building.

On January 6, 2021, a group of “patriots,” in the name of respect for our country’s founding principles, mobbed an honored government building, attacked fellow citizens who defended the building, even stabbing one with a metal fence stake,8 and for hours “vandalized and looted the interior and ransacked offices as they searched for their perceived enemies in Congress.”9

Were these people truly acting in the name of respect for our country, or were they relishing in disrespectful, irresponsible, and dehumanizing self-indulgence?

Of course, there’s a time and place for elevating the worth of a principle and being willing to sacrifice for it. But there’s a way to go about promoting one principle, without rationalizing away our other principles. Glover, in Humanity cautions:

When terrible orders are given, some people resist because of their conception of who they are. But there may be no resistance when a person’s self-conception has been built round obedience. … A lot depends on how far the sense of moral identity has been narrowed to a merely tribal or ideological one.10

Too much respect can lead one to blindly follow orders, to get swept up in a group identity, or to devalue other humans and their own principles in the name of promoting a cause.

Navigating the gray areas

To keep ourselves on the moral end of the gray areas, we can ask ourselves some questions that get to the truth about people’s motivations, the level of respect we’re demonstrating, and whether we’re being responsible and compassionate in how we treat other people.

Are people being treated with dignity, care, and fairness? Would the action seem respectful if it were directed at me or my group?

Are any cognitive distortions (chapter 2) or Us-and-Them biases (chapter 8) at work that might cause someone to over-inflate or downplay the harm that’s being done?

Is my response, or my group’s response, being true to principles of respect for all people, even the ones we disagree with? Does the response work toward true justice and equality, or is there an element of vengeance to our actions?

A path forward

We have a common conception about what the right amount of respect is. It starts with our fundamental obligation to treat each other with care and dignity. The danger of too little respect is obvious—the worst atrocities of our time were enabled by devaluing and dehumanizing. Yet today, too much respect for tribal identities and causes is ironically leading to acts of disrespect toward our principles and other people. If we want stability, we need to come back to our shared sense of who we are, not as tribal factions, but as humans, rooted in decency. We need to remember and honor our unspoken commitment of respect for each other:

I will treat you with the care and dignity you deserve, and in return, I expect you will treat me with the care and dignity I deserve as a fellow human.

Excerpt reprinted from the book Rooted in Decency with the author's permission. © 2022 Colleen Doyle Bryant.

Buy the Book

Journaling

Explore your thoughts with these journaling prompts:

- What do you respect? What are things you feel have value and should be treated with care?

- Have you ever agreed with something because it was reasonable, even if it wasn’t what you would have preferred?

- Have you seen examples of people allowing their admiration for a person or cause to blind them?

Want to read more?

Buy the print or ebook and start your journey.

Sources

Endnotes- Chapter 17: What is Respect?

1. Robin S. Dillon, Respect, In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University 2018).

2. Sources for definition and discussion of degrees of respect

- My experience writing books and teaching resources on respect: see Bryant, n.d.-d in the references list.

- The world belief systems in chapter 12 of this book, Rooted in Decency.

- General sources on respect, human dignity, fairness:

Robin S. Dillon, Respect.

Jonathan Glover, Humanity: A moral history of the twentieth century (Second Edition) (Yale Univ. Press 2012, Originally published 1999).

Immanuel Kant, The metaphysics of morals (M. Gregor, Ed. & Trans.) (Cambridge University Press 1996, Originally published 1797).

John Rawls, Justice as fairness: A restatement (E. Kelly, Ed.) (Belknap Press 2001).

Jonathan Sacks, Morality: Restoring the common good in divided times (Basic Books 2020).

3. Brian Duignan, John Rawls, Encyclopedia Britannica, 2022, February 17.

4. John Rawls, Justice as fairness, §2.2.

5. John Rawls, Justice as fairness, §2.2.

6.Jonathan Haidt, Wired to be Inspired, Greater Good Science Center, 2005, March 1.

7.For specifics accounts of student protests, see Greg Lukianoff & Jonathan Haidt, The coddling of the American mind: How good intentions and bad ideas are setting up a generation for failure (Penguin 2018) and Justin Folk (Director), No Safe Spaces [Film] (Atlas 2019).

8. Tom Jackman, Police Union says 140 officers injured in Capitol Riot, Washington Post, 2021, January 27.

9. Brian Duignan, United States Capitol attack of 2021, Encyclopedia Britannica, 2022, January 6.

10. Jonathan Glover, Humanity, p. 404.

Note: This page contains affiliate links.